The XSF format is internal

XCrySDen structure format. XSF

stands for

XCrySDen

Structure File. It is used to describe (i) molecular and

crystal structure, (ii) forces acting on constituent atoms, and

(iii) scalar fields (for example: charge density, electrostatic

potential). The main attributes of XSF format are:

- all records are in free format

- the XSF formatted file is composed from various sections

- each sections begins with the keyword

- there are two types of keywords: (i) single keywords,

and (ii) sandwich keywords, which are defined as:

- single keyword: section begins with a single keyword

and ends without an end-keyword

- sandwich keyword: section begins with a begin-keyword

(i.e.

BEGIN_keyword) and ends with an end-keyword

(i.e. END_keyword), where keyword is one

among keywords.

- all coordinates are in ANGSTROMS units

- all forces are in Hartree/ANGSTROM units

- the comment-lines start with the "#" character (see below)

The comment-lines were introduced to the XSF file starting from

XCrySDen version 1.4.

The comment-lines start with the

"#" character; comments are

allowed only between sections and not within a given section. Here

are two examples (correct and incorrect).

Correct example (comments are bewteen the sections):

# this is a specification

# of ZnS crystal structure

CRYSTAL

# these are primitive lattice vectors (in Angstroms)

PRIMVEC

2.7100000000 2.7100000000 0.0000000000

2.7100000000 0.0000000000 2.7100000000

0.0000000000 2.7100000000 2.7100000000

# these are convetional lattice vectors (in Angstroms)

CONVVEC

5.4200000000 0.0000000000 0.0000000000

0.0000000000 5.4200000000 0.0000000000

0.0000000000 0.0000000000 5.4200000000

# these are atomic coordinates in a primitive unit cell

# (in Angstroms)

PRIMCOORD

2 1

16 0.0000000000 0.0000000000 0.0000000000

30 1.3550000000 -1.3550000000 -1.3550000000

|

Incorrect example (comment is within the section):

ATOMS

6 2.325243 -0.115261 0.031711

1 2.344577 -0.363301 1.077589

#

# this is a comment on the wrong place

#

6 0.007719 -0.041269 0.244204

9 0.064656 1.154700 0.824420

9 -0.042641 -0.911850 1.255074

8 -1.071578 -0.152842 -0.539134

|

For MOLECULES the XSF format is very simple. The first line begins

with the

ATOMS keyword and then one specifies the

structural data for all atoms. An entry for an atom looks like:

AtNum X Y Z

where

AtNum stands for atomic number (or symbol),

while

X Y Z are Cartesian coordinates in ANGSTROMS

units. Here is one example:

ATOMS

6 2.325243 -0.115261 0.031711

1 2.344577 -0.363301 1.077589

9 3.131708 -0.909527 -0.638930

9 2.736189 1.130568 -0.134093

8 1.079338 -0.265162 -0.526351

6 0.007719 -0.041269 0.244204

9 0.064656 1.154700 0.824420

9 -0.042641 -0.911850 1.255074

8 -1.071578 -0.152842 -0.539134

6 -2.310374 0.036537 0.022189

1 -2.267004 0.230694 1.077874

9 -2.890949 1.048938 -0.593940

9 -3.029540 -1.046542 -0.203665

|

The XSF format allows to specify structures of different

periodicity. The keywords

MOLECULE,

POLYMER,

SLAB, and

CRYSTAL

designate the 0-, 1-, 2-, and 3-dimensional structures (i.e.

periodic dimensions are meant here). For crystal structures the

file begin with

CRYSTAL keyword. Then one needs to

specify the lattice vectors and the atoms belonging to the unit

cell.

XCrySDen accepts

two different setting of the unit cell. These are usually called

the primitive and the conventional unit cell. The corresponding

keywords are

PRIMVEC for primitive lattice vectors and

PRIMCOORD for atoms belonging to the primitive unit

cell. The

CONVVEC and

CONVCOORD have the

analogous meaning for the conventional unit cell.

Warning:

in XSF file the two settings of the unit cell are supposed to have

the same origin. If you want to specify some crystal structure with

two settings of the unit cell, that have different origins you will

have to create two XSF files. In practice only

PRIMVEC,

PRIMCOORD and

CONVVEC need to be specified, and then "conventional

coordinates" (

CONVCOORD) are generated by

XCrySDen itself, hence it is

never needed to specify the

CONVCOORD section

!!! Here is an example of ZnS crystal structure:

CRYSTAL see (1)

PRIMVEC

0.0000000 2.7100000 2.7100000 see (2)

2.7100000 0.0000000 2.7100000

2.7100000 2.7100000 0.0000000

CONVVEC

5.4200000 0.0000000 0.0000000 see (3)

0.0000000 5.4200000 0.0000000

0.0000000 0.0000000 5.4200000

PRIMCOORD

2 1 see (4)

16 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 see (5)

30 1.3550000 -1.3550000 -1.3550000

|

| Legend: |

| (1) |

this keyword specify the structure is

crystal

|

| (2) |

specification of PRIMVEC (in

ANGSTROMS) like:

ax, ay,

az (first lattice vector)

bx, by,

bz (second lattice vector)

cx, cy,

cz (third lattice vector)

|

| (3) |

specification of CONVVEC (see

(2))

|

| (4) |

First number stands for number of atoms in the

primitive cell (2 in this case). The second number is always

1 for PRIMCOORD coordinates.

|

| (5) |

Specification of atoms in the primitive cell

(the same as for ATOMS section).

|

All that is needed to specify the forces acting on atoms is to

supplement the appropriate coordinate section (

ATOMS

or

PRIMCOORD). Now an entry for an atom would look

like:

AtNum X Y Z Fx Fy Fz

where

Fx Fy Fz stands for force components in X, Y and

Z direction, respectively. The force components are expressed in

Cartesian coordinate system in Hartree/ANGSTROM unit. Here is an

example of water molecule:

ATOMS

8 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 -.05164 .00000 -.03999

1 0.00000 0.00000 1.00000 .01769 .00000 .03049

1 0.96814 0.00000 -0.25038 .03395 .00000 .00949

|

And here is an example for the periodic structure structure:

SLAB

PRIMVEC

5.8859828533 0.0000000000 0.0000000000

0.0000000000 5.8859828533 0.0000000000

0.0000000000 0.0000000000 1.0000000000

PRIMCOORD

11 1

6 3.674759 2.942992 -3.493103 -0.021668 0.000000 -0.057324

1 4.121990 3.816734 -4.007689 -0.000478 0.001204 0.006657

1 4.121990 2.069250 -4.007689 -0.000478 -0.001204 0.006657

6 2.211226 2.942992 -3.493103 0.021668 0.000000 -0.057324

1 1.763995 3.816734 -4.007689 0.000478 0.001204 0.006657

1 1.763995 2.069250 -4.007689 0.000478 -0.001204 0.006657

8 0.000000 0.000000 -2.719012 0.000000 0.000000 -0.050242

47 4.448147 4.449892 -1.919011 -0.022812 -0.029123 0.007553

47 4.448147 1.436093 -1.919011 -0.022812 0.029123 0.007553

47 1.437838 4.449892 -1.919011 0.022812 -0.029123 0.007553

47 1.437838 1.436093 -1.919011 0.022812 0.029123 0.007553

|

It is possible to specify several snapshots of a structure in the

XSF format. For example: the file can contain the data for all

structures that were created during an optimization run or

molecular-dynamics run. These structures can be displayed as

animation by

XCrySDen.

The main attributes of the animated XSF format are:

- the AXSF file begins with the

ANIMSTEPS

nstep keyword, where nstep

stands for number of animation steps.

- number of atoms for all steps must be the same

!!!

- in fixed-cell animated XSF for crystal structures the unit cell

for all steps is taken to be the same

- in variable-cell animated XSF for crystal structures the unit

cell is specified for each animation step

- the

ATOMS and PRIMCOORD keywords are

prefixed by an integer number which is the sequential index of a

given snapshot. Therefore the syntax is ATOMS

istep and PRIMCOORD

istep.

- for variable-cell crystal structure the

PRIMVEC

and CONVVEC keywords are prefixed with sequential

index.

Here is an example of AXSF file. It shows different structures

during an optimization of water molecule. Note the index prefixes

after

ATOMS keywords.

ANIMSTEPS 4

ATOMS 1

8 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -0.0516 0.0000 -0.0399

1 0.0000 0.0000 1.0000 0.0176 0.0000 0.0304

1 0.9681 0.0000 -0.2503 0.0339 0.0000 0.0094

ATOMS 2

8 -0.1480 0.0000 -0.1146 0.0020 0.0000 0.0015

1 -0.0468 0.0000 0.9134 -0.0069 0.0000 0.0069

1 0.8726 0.0000 -0.2740 0.0049 0.0000 -0.0084

ATOMS 3

8 -0.1032 0.0000 -0.0799 0.0013 0.0000 0.0010

1 -0.0319 0.0000 0.9591 0.0011 0.0000 -0.0028

1 0.9205 0.0000 -0.2710 -0.0025 0.0000 0.0018

ATOMS 4

8 -0.1102 0.0000 -0.0853 0.0001 0.0000 0.0000

1 -0.0345 0.0000 0.9503 -0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000

1 0.9114 0.0000 -0.2714 -0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000

|

Here is an example of animated XSF for the ZnS crystal structure

with the fixed unit-cell. Note the index prefixes after

PRIMCOORD keywords.

ANIMSTEPS 2

CRYSTAL

PRIMVEC

0.0000000 2.7100000 2.7100000

2.7100000 0.0000000 2.7100000

2.7100000 2.7100000 0.0000000

PRIMCOORD 1

2 1

16 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000

30 1.3550000 -1.3550000 -1.3550000

PRIMCOORD 2

2 1

16 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000

30 1.2550000 -1.2550000 -1.2550000

|

Here is an example of animated XSF for the ZnS crystal structure

with the variable unit-cell. Note the index prefixes after

PRIMVEC,

CONVVEC, and

PRIMCOORD keywords.

ANIMSTEPS 2

CRYSTAL

PRIMVEC 1

2.7100000 2.7100000 0.00000000

2.7100000 0.0000000 2.71000000

0.0000000 2.7100000 2.71000000

CONVVEC 1

5.4200000 0.0000000 0.00000000

0.0000000 5.4200000 0.00000000

0.0000000 0.0000000 5.42000000

PRIMCOORD 1

2 1

16 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.00000000

30 1.3550000 -1.3550000 -1.35500000

PRIMVEC 2

2.9810000 2.9810000 0.00000000

2.9810000 0.0000000 2.98100000

0.0000000 2.9810000 2.98100000

CONVVEC 2

5.9620000 0.0000000 0.00000000

0.0000000 5.9620000 0.00000000

0.0000000 0.0000000 5.96200000

PRIMCOORD 2

2 1

16 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.00000000

30 1.5905000 -1.5905000 -1.59050000

|

It is possible to specify one or several scalar fields (both 2D and

3D) as an

uniform mesh of values in the XSF formatted file.

The mesh can be

non-orthogonal. This scalar field meshes are

called

datagrids.

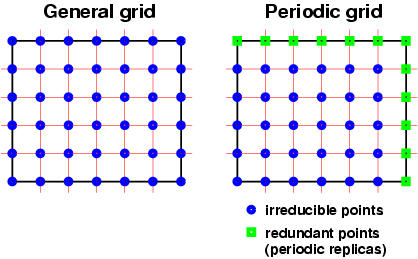

Datagrids in

XCrySDen

are general grids and not periodic one!!! What is meant by this

will be explained bellow. A general grid is a uniform grid that is

spanned inside some box, which is either non-orthogonal or

orthogonal. For a molecule such a box would be a bounding box,

while for crystal such a box would be a unit cell. However in a

grid that span a whole unit-cell some border points would be

redundant due to translational symmetry. Grids that omit these

redundant points are called periodic (by this convention a FFT

(fast-Fourier transform) mesh would be a periodic mesh). The

general vs. periodic grid concept is shown graphically here:

Note: datagrids in

XCrySDen are general grids !!!

The datagrid section is structured and organized in blocks. The

grids inside a block can be manipulated among themselves by

XCrySDen program. The

main attributes of XSF datagrids are:

| (1) |

the top datagrid section is called

BLOCK_DATAGRID and is sandwiched between

BEGIN_BLOCK_DATAGRID_xD and

END_BLOCK_DATAGRID_xD keywords, where x

stands for the dimensionality of the grid. Currently 2D and 3D

scalar grids are supported.

|

| (2) |

there can be an arbitrary number of

BLOCK_DATAGRID sections.

|

| (3) |

there can be an arbitrary number of datagrids

inside one BLOCK_DATAGRID section. All datagrids belonging to the

same BLOCK_DATAGRID must have the dimensionality as defined by

BEGIN_BLOCK_DATAGRID_xD keyword. These datagrids must

also share the following properties: (i) they should span the same

space (origin and the spanning vectors must be the same), and (ii)

they should have the same number of data-points. Each datagrid in a

BLOCK_DATAGRID is sandwiched inside

BEGIN_DATAGRID_xD_identifier and

END_DATAGRID_xD keywords, where x stands

for dimensionality of the grid and the identifier is

used as an identifier of the datagrid.

|

| (4) |

after the BEGIN_BLOCK_DATAGRID_xD

keyword and before the first DATAGRID_xD_identifier

keyword is a comment, which is used as an identifier for the

BLOCK_DATAGRID. It must be a single word!!!

|

| (5) |

the values inside a datagrid are specified in

column-major (i.e. FORTRAN) order. This means that values are

written as:

- C-syntax:

for (k=0; k<nz; k++)

for (j=0; j<ny; j++)

for (i=0; i<nx; i++)

printf("%f",value[i][j][k]);

- FORTRAN syntax:

write(*,*)

$ (((value(ix,iy,iz),ix=1,nx),iy=1,ny),iz=1,nz)

|

Above specifications may sound very fuzzy, hence let us clarify

this by looking at a very simple example. The

description of all records follows

after the example. Also take a look at

schematic presentation of the structure of

datagrids of below example.

l.01

l.02

l.03

l.04

l.05

l.06

l.07

l.08

l.09

l.10

l.11

l.12

l.13

l.14

l.15

l.16

l.17

l.18

l.19

l.20

l.21

l.22

l.23

l.24

l.25

l.26

l.27

l.28

l.29

l.30

l.31

l.32

l.33

l.34

l.35

l.36

l.37

l.38

l.39

l.40

l.41

l.42

l.43

l.44

l.45

l.46

l.47

l.48

l.49

l.50

l.51

l.52

l.53

l.54

l.55

l.56

l.57

l.58

l.59

l.60

l.61

l.62

l.63

l.64

l.65

|

BEGIN_BLOCK_DATAGRID_2D

my_first_example_of_2D_datagrid

BEGIN_DATAGRID_2D_this_is_2Dgrid#1

5 5

0.0 0.0 0.0

1.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 1.0 0.0

0.000 1.000 2.000 5.196 8.000

1.000 1.414 2.236 5.292 8.062

2.000 2.236 2.828 5.568 8.246

3.000 3.162 3.606 6.000 8.544

4.000 4.123 4.472 6.557 8.944

END_DATAGRID_2D

BEGIN_DATAGRID_2D_this_is_2Dgrid#2

5 5

0.0 0.0 0.0

1.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 1.0 0.0

4.000 4.123 4.472 6.557 8.944

3.000 3.162 3.606 6.000 8.544

2.000 2.236 2.828 5.568 8.246

1.000 1.414 2.236 5.292 8.062

0.000 1.000 2.000 5.196 8.000

END_DATAGRID_2D

END_BLOCK_DATAGRID_2D

BEGIN_BLOCK_DATAGRID_3D

my_first_example_of_3D_datagrid

BEGIN_DATAGRID_3D_this_is_3Dgrid#1

5 5 5

0.0 0.0 0.0

1.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 1.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 1.0

0.000 1.000 2.000 5.196 8.000

1.000 1.414 2.236 5.292 8.062

2.000 2.236 2.828 5.568 8.246

3.000 3.162 3.606 6.000 8.544

4.000 4.123 4.472 6.557 8.944

1.000 1.414 2.236 5.292 8.062

1.414 1.732 2.449 5.385 8.124

2.236 2.449 3.000 5.657 8.307

3.162 3.317 3.742 6.083 8.602

4.123 4.243 4.583 6.633 9.000

2.000 2.236 2.828 5.568 8.246

2.236 2.449 3.000 5.657 8.307

2.828 3.000 3.464 5.916 8.485

3.606 3.742 4.123 6.325 8.775

4.472 4.583 4.899 6.856 9.165

3.000 3.162 3.606 6.000 8.544

3.162 3.317 3.742 6.083 8.602

3.606 3.742 4.123 6.325 8.775

4.243 4.359 4.690 6.708 9.055

5.000 5.099 5.385 7.211 9.434

4.000 4.123 4.472 6.557 8.944

4.123 4.243 4.583 6.633 9.000

4.472 4.583 4.899 6.856 9.165

5.000 5.099 5.385 7.211 9.434

5.657 5.745 6.000 7.681 9.798

END_DATAGRID_3D

END_BLOCK_DATAGRID_3D

|

| Legend: |

| l.01 |

beginning of 2D block of

datagrids

|

| l.02 |

one word comment - used as an identifier for

this block

|

| l.03 |

beginning of the first 2D datagrid in a

block

|

| l.04 |

number of data-points in each direction (i.e.

nx ny for 2D grids)

|

| l.05 |

origin of the datagrid

|

| l.06 |

first spanning vector of the datagrid

|

| l.07 |

second spanning vector

|

| l.08-12 |

5x5 datagrid values in column-major mode

|

| l.13 |

end of the first 2D datagrid in a block

|

| l.14-24 |

these lines specify second 2D datagrid in a

block in totally analogous manner as the first 2D datagrid.

|

| l.25 |

end of 2D block of datagrids

|

| |

|

| l.27 |

beginning of 3D block of

datagrids

|

| l.28 |

one word comment - used as an identifier for

this block

|

| l.29 |

beginning of the first 3D datagrid in a

block

|

| l.30 |

number of data-points in each direction (i.e.

nx ny nz for 3D grids)

|

| l.31 |

origin of the datagrid

|

| l.32 |

first spanning vector of the datagrid

|

| l.33 |

second spanning vector

|

| l.34 |

third spanning vector

|

| l.35-63 |

5x5x5 datagrid values in column-major

mode

|

| l.64 |

end of the first 3D datagrid in a block

|

| l.65 |

end of 3D block of datagrids

|

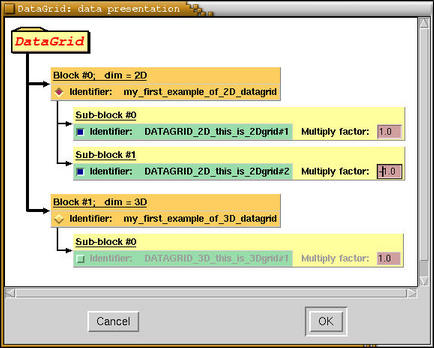

Here is a scheme of the structure of datagrids of above example as

displayed by

XCrySDen

program.

Bandgrids are variation on a theme of datagrids. They were

introduced for the visualization of Fermi surfaces and yields a

simplified format of

datagrids. Please notice that despite

their purpose they are still

general grids

and not periodic ones. The

bandgrid for the visualization

of Fermi surface should be defined as:

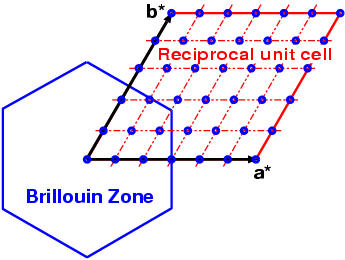

Please notice that the bandgrid span the reciprocal unit cell, not

the Brillouin zone !!! Points are later translated back to

Brillouin zone by

XCrySDen and Fermi surface is

rendered inside the Brillouin zone.

Warning: so far

XCrySDen uses

bandgrids solely for the visualization of Fermi surfaces

(the coresponding files are called BXSF, standing for Band-XSF). If

you want to render some other property as contours/isosurfaces you

must specify the scalar fields as

datagrids. This is

because the Fermi surfaces needs some special processing and

therefore bandgrids are automatically processed. The main

attributes of

bandgrids are:

| (1) |

the structure of bandgrids is similar

to datagrids

|

| (2) |

there can only be one BLOCK_BANDGRID

section

|

| (3) |

there can only be one BANDGRID in

BLOCK_BANDGRID

|

| (4) |

there can be an arbitrary number of

bands inside BANDGRID section, where BAND is ...

|

| (5) |

so far only 3D bandgrids are

supported

|

| BEWARE: |

the values inside a bandgrid are specified in

row-major (i.e. C) order. This

means that values are written as:

- C-syntax:

for (i=0; i<nx; i++)

for (j=0; j<ny; j++)

for (k=0; k<nz; k++)

printf("%f",value[i][j][k]);

- FORTRAN syntax:

write(*,*)

$ (((value(ix,iy,iz),iz=1,nz),iy=1,ny),ix=1,nx)

|

Here is a

bandgrid example. The description of the records

is below the example.

l.01

l.02

l.03

l.04

l.05

l.06

l.07

l.08

l.09

l.10

l.11

l.12

l.13

l.14

l.15

l.16

l.17

l.18

l.19

l.20

l.21

l.22

l.23

l.24

l.25

l.26

l.27

l.28

l.29

l.30

l.31

l.32

l.33

l.34

l.35

l.36

l.37

l.38

l.39

l.40

l.41

l.42

l.43

l.44

l.45

l.46

l.47

l.48

l.49

l.50

l.51

l.52

l.53

l.54

l.55

l.56

l.57

l.58

l.59

l.60

l.61

l.62

l.63

|

BEGIN_INFO

#

# this is a sample Band-XCRYSDEN-Structure-File

# aimed for Visualization of Fermi Surface

#

# Case: just an example

#

# Launch as: xcrysden --bxsf example.bxsf

#

Fermi Energy: 0.83511

END_INFO

BEGIN_BLOCK_BANDGRID_3D

here_we_have_some_examples

BEGIN_BANDGRID_3D_simple_example

2

4 4 4

0.0 0.0 0.0

1.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 1.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 1.0

BAND: 3

0.000 0.192 0.385 0.577

0.192 0.272 0.430 0.609

0.385 0.430 0.544 0.694

0.577 0.609 0.694 0.816

0.192 0.272 0.430 0.609

0.272 0.333 0.471 0.638

0.430 0.471 0.577 0.720

0.609 0.638 0.720 0.839

0.385 0.430 0.544 0.694

0.430 0.471 0.577 0.720

0.544 0.577 0.667 0.793

0.694 0.720 0.793 0.903

0.577 0.609 0.694 0.816

0.609 0.638 0.720 0.839

0.694 0.720 0.793 0.903

0.816 0.839 0.903 1.000

BAND: 4

1.000 0.942 0.885 0.827

0.942 0.918 0.871 0.817

0.885 0.871 0.837 0.792

0.827 0.817 0.792 0.755

0.942 0.918 0.871 0.817

0.918 0.900 0.859 0.809

0.871 0.859 0.827 0.784

0.817 0.809 0.784 0.748

0.885 0.871 0.837 0.792

0.871 0.859 0.827 0.784

0.837 0.827 0.800 0.762

0.792 0.784 0.762 0.729

0.827 0.817 0.792 0.755

0.817 0.809 0.784 0.748

0.792 0.784 0.762 0.729

0.755 0.748 0.729 0.700

END_BANDGRID_3D

END_BLOCK_BANDGRID_3D

|

| Legend: |

| l.01 |

beginning of INFO section

|

| l.02-09 |

a hash "#" character stands for comment

|

| l.10 |

a "Fermi Energy:" string is a

marker for reading the value of Fermi energy

|

| l.11 |

end of INFO section

|

| |

|

| l.13 |

beginning of 3D block of

bandgrids

|

| l.14 |

one word comment - used as an identifier for

this block

|

| l.15 |

beginning of the 3D bandgrid

|

| l.16 |

number of bands in the bandgrid

|

| l.17 |

number of data-points in each direction (i.e.

nx ny nz for 3D grids)

|

| l.18 |

origin of the bandgrid

Warning: origin should be (0,0,0) (i.e. Gamma point)

|

| l.19 |

first spanning vector of the bandgrid (i.e.

first reciprocal lattice vector)

|

| l.20 |

second spanning vector

|

| l.21 |

third spanning vector

|

| l.22 |

beginning of the BAND with label 3

|

| l.23-41 |

4x4x4 values in row-major mode

|

| l.42 |

beginning of the BAND with label 4

|

| l.43-61 |

4x4x4 values in row-major mode

|

| l.62 |

end of the bandgrid

|

| l.63 |

end of 3D bandgrid block

|

![[Figure]](img/xcrysden-picture-small-new.jpg)

![[Figure]](img/xcrysden-picture-small-new.jpg)